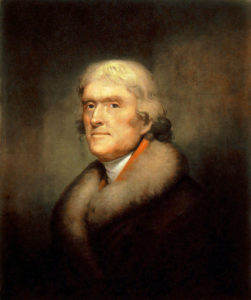

People remember Thomas Jefferson mainly for the Declaration of Independence, which he wrote in 1776. Some remember that he served as president from 1801 to 1809, but aside from that, few know much more of his life and work. In fact, he lived and worked until 1826, when he died on July 4th, fifty years to the day after the ratification of his Declaration.

People remember Thomas Jefferson mainly for the Declaration of Independence, which he wrote in 1776. Some remember that he served as president from 1801 to 1809, but aside from that, few know much more of his life and work. In fact, he lived and worked until 1826, when he died on July 4th, fifty years to the day after the ratification of his Declaration.

What’s lost to history is that Jefferson was convinced Americans were losing their fight for freedom.

Consolidation

In his last years, after a lifetime of learning and experience, Jefferson had one thing preeminently on his mind: the principle of decentralization.

Jefferson didn’t use the words “centralization” or “decentralization,” of course. Rather, he used the common words of his time: consolidation and distribution. Obviously they meant the same things.

Here’s a direct statement on the subject, from his autobiography, written in 1821:

It is not by the consolidation, or concentration, of powers, but by their distribution, that good government is effected.

This statement put Jefferson at odds with political leaders, as he writes in a letter to Judge William Johnson in 1823:

I have been blamed for saying that a prevalence of the doctrines of consolidation would one day call for reformation or revolution.

The following passage is from a letter to Judge Johnson, written in 1822:

Finding that monarchy is a desperate wish in this country, they [successors to the Federalist Party] rally to the point which they think next best, a consolidated government. Their aim is now, therefore, to break down the rights reserved by the Constitution to the States as a bulwark against that consolidation, the fear of which produced the whole of the opposition to the Constitution at its birth.

Notice his primary points:

-

- Political parties were pursuing centralization, as was in their interest.

-

- The parties were trying to steal the power of the individual States and to centralize it in one city. Furthermore that they were degrading the Constitution to do so.

In a letter to William T. Barry in 1822, Jefferson refers to the Marbury v. Madison decision of 1803, a decision that American schoolchildren are taught to revere. Jefferson, however, considered it a disaster. He writes,

The foundations are already deeply laid by [the Supreme Court’s] decisions for the annihilation of constitutional State rights, and the removal of every check, every counterpoise to the engulfing power of which themselves are to make a sovereign part.

If ever this vast country is brought under a single government, it will be one of the most extensive corruption, indifferent and incapable of a wholesome care over so wide a spread of surface.

The Marbury v. Madison decision was beyond all else astonishing, because it maintained that the man who wrote the Constitution, James Madison, didn’t understand it!

More importantly, however, it granted the right to interpret the constitution to the Supreme Court, taking that right away from the states. The decision consolidated power in Washington.

It’s also central to this point that both Jefferson and Madison – the authors of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution respectively – were so concerned over this that they wrote resolutions in 1798 (the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions) to preserve the constitutional position of the states, which was being overridden by the Federalist party during the presidency of John Adams.

Here is one final passage from Jefferson, from a letter to William B. Giles in 1825, half a year before his death:

I see… with the deepest affliction, the rapid strides with which the federal branch of our government is advancing towards the usurpation of all the rights reserved to the States, and the consolidation in itself of all powers, foreign and domestic; and that too, by constructions which, if legitimate, leave no limits to their power.

The Man Was Right

Jefferson wasn’t right on every detail, of course, and the path to consolidation had some detours, but overall he was quite correct:

Lincoln’s Civil War enslaved the states to the national government (nothing in the Constitution forbids secession) and the events of 1913 (the income tax, stripping the states of their power to appoint senators, and a central bank) brought the entire nation, from ocean to ocean, under the control of a single city.

And so the United States became something like an empire, even though (thankfully) some decentralization remains.

The American nation wasn’t designed to be this way. Jefferson saw it coming and warned us.

**

If you’d like to see what Jefferson, Madison, Washington, Adams and the rest actually said, in their own words, please see The Words Of The Founders.

**

Paul Rosenberg

freemansperspective.com